All cements and mortars contain alkali hydroxides. Aggregates contain silica, a major constituent of sand that’s also found in quartz, granite, and other rock.

Water sets off a chemical reaction between sodium hydroxide (NaOH) in the cement and certain silicates, primarily opaline chert, strained quartz and borosilicates, in aggregate. This chemical reaction forms an expansive gel that can produce enough pressure to crack concrete.

This process – alkali-silica reaction (ASR) – is the beginning of the end for pavement integrity. Once even microscopic cracking begins, water seeps into the slab, where it freezes and expands, further cracking the concrete. Over time, the water and any chlorides that were used to deice the pavement’s surface reach the slab’s steel reinforcement. The rebar expands as it rusts, further exacerbating cracking and deterioration.

Cracking usually appears in areas with a frequent supply of moisture. Common locations include close to the waterline on piers, near the ground behind retaining walls, near joints and free edges in pavement, and in piers or columns subject to wicking actions.

This photo shows typical ASR damage: random “map” cracking. In advanced cases, you see closed joints and attendant spalling. Cracking also tends to occur in the middle rather than the edges of pavement slabs.

Comparison: Portland Cement vs. Rapid Set® Cement

Laboratory testing and examination of Rapid Set® concrete pavement 25 years and older show no discernible ASR cracking or ASR gel in the microstructure of the cement-aggregate matrix.

Why is this?

Several studies suggest that the presence of aluminum (Al) in calcium sulfoaluminate (CSA) cements like Rapid Set® helps mitigate ASR by safeguarding the boundaries of the aggregate grains. Rapid Set® also consumes virtually all the water in the matrix, which also reduces the potential for ASR.

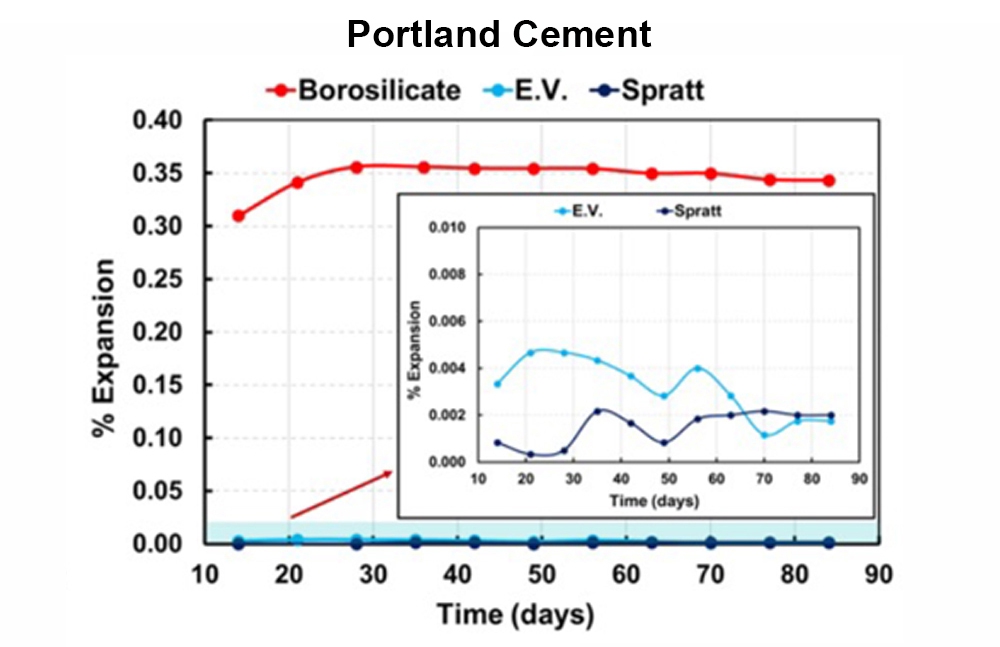

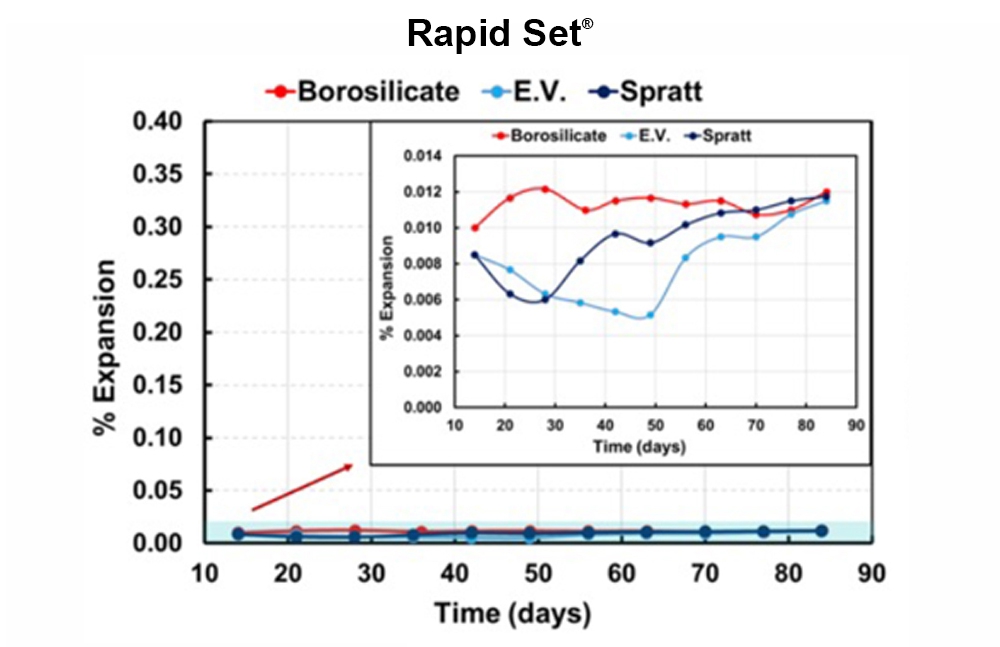

To see how aggregate chemistry affects the binder in ordinary portland cement (OPC) and Rapid Set®, we followed ASTM C441 testing protocol to determine each cement’s reaction to aggregate – relatively unreactive Eagle Valley Aggregates (E.V.) from California and mildly reactive Spratt Aggregates from Canada – as well as highly reactive borosilicate.

Not surprisingly, both cements perform very well with both innocuous and mildly reactive aggregates.

However, portland cement expands approximately 30 times more than Rapid Set® in the presence of highly reactive borosilicate. Here’s a chart illustrating this result.

Whereas, as the chart below demonstrates, Rapid Set® experiences minimal expansion with all three aggregates.

Thus, Rapid Set® makes it possible to use aggregates that would otherwise be considered unusable due to their high potential for silica reaction.